Over the last couple of years, there’s been a huge amount of hype around AI in general, and specifically around using it to help with research and writing. There are countless AI platforms promising to make life easier for PhD students and researchers, and many supposed experts extolling their virtues.

In some ways, the technology is very impressive, and I think that it can, potentially, be used effectively and ethically in research. But I think it should only be used for certain things, and you shouldn’t allow yourself to become dependent on it.

As I mentioned in a previous video, I started my PhD in 2003. This means that I’m closer to the generation that had to go to the library and find papers by hand than the current generation with all the current online tools. Google scholar didn’t even exist1 until about a year after I started, just to give one example.

While technology absolutely helps, and I’m not suggesting for a moment that you shouldn’t use tech when appropriate, you still need to be able to identify, read and understand relevant papers and you still need to be able to write about the literature and your own work.

These fundamentals have not changed, and while AI might be able to supplement these skills, it cannot replace them.

Unfortunately, because these skills are generally so badly taught, AI provides an easy shortcut, both for students under pressure and for supposed experts who don’t seem to have any other meaningful insight, but can churn out videos on the latest tools.

In the short term, these AI platforms might seem to be the answer to your prayers, in that they can very quickly produce work that looks good on superficial reading. But the danger is that while it gets many things right, it also makes wild mistakes.

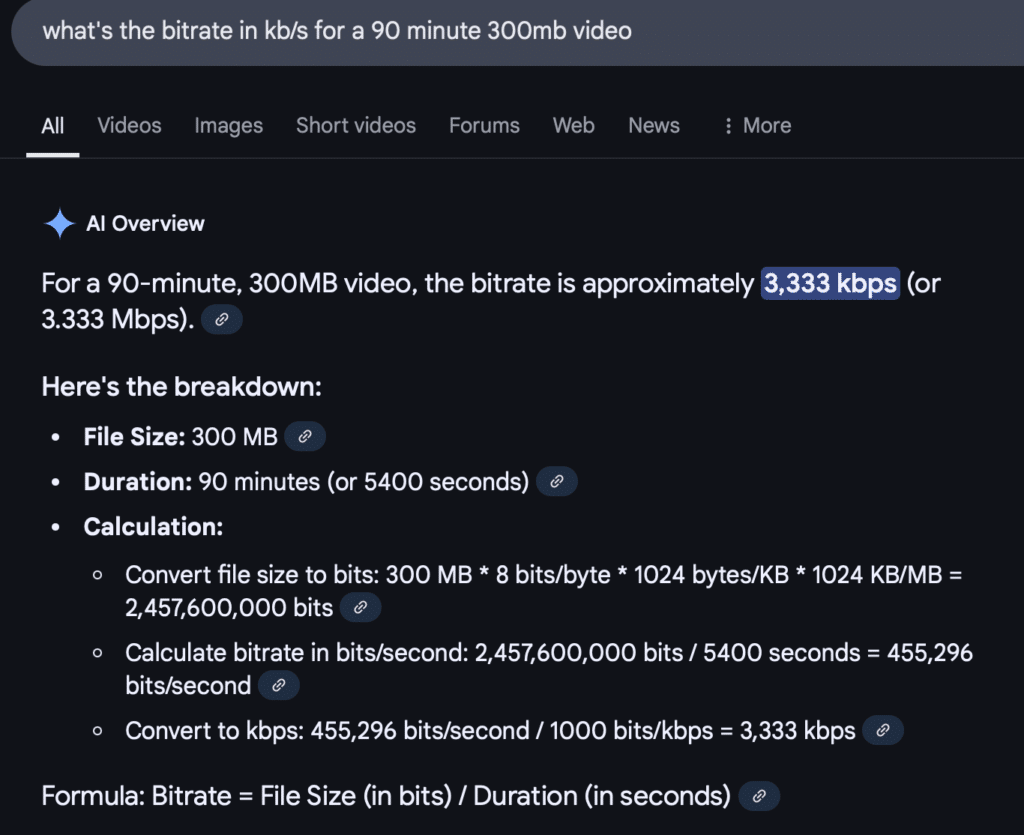

To give just one example, I recently used google to try to calculate the bitrate per second for one of my videos. The AI bot produced an answer and it provided the working, but the answer was very obviously wrong and it seemed to just be imitating the kind of logic that you’d need to use, using the right sort of language, but getting it completely wrong on every level.

This was for a calculation that just involved converting some units and dividing one number by another.

In this case, I could see it was wrong straight away and could do the calculation myself quite easily, but imagine if it was something my PhD depended upon, but I didn’t notice the mistakes. An examiner would have noticed. And if I couldn’t defend what I’d submitted in my name then it would, quite rightly, raise suspicion about everything else I’d written.

You have to be able to defend anything and everything you submit in your own name. If you don’t have the skill or expertise to do something yourself, or to check what AI has done on your behalf, it’s just so risky to blindly trust it.

Even if you get away with it, what if somebody finds it later? There have been plenty of high profile cases of people losing their jobs years after graduation because of plagiarism or other forms of dishonesty in their PhD theses, and AI just increases this risk by making cheating much easier.

There are plenty of posts out there explaining at length how to avoid having your text flagged as generated by AI, but the best way to avoid having your text flagged as generated by AI is to not use AI to generate your text.

This means you need to develop your knowledge and your writing skills, but isn’t that why you started a PhD in the first place? Besides, if you did want to use AI to help with writing, to proofread or to tidy up the text, you still need to be able to write.

If your original text doesn’t clearly communicate what you want it to, then AI cannot read your mind to understand what you intended to say.

Very often, when I read students’ work, the text on the page doesn’t match what they’ve explained to me in conversation and it takes some time to figure out what they actually want to get across. AI will do it faster, but if the input wasn’t already good, then the output won’t be either, and if the information wasn’t on the page then AI can’t fill those gaps.

Again, it might look good on the surface, but it doesn’t take much digging to figure out that you didn’t write it or to find mistakes. I can often spot them when I don’t know the subject that well, so a good examiner who’s a specialist in the field will tear you to pieces, and rightly so.

At an individual level, people will get away with it. There have always been cheats and lazy people in academia, but there are deeper problems with the widespread use of AI in academia that we need to think about.

If AI is being used to generate papers, both in terms of the written text and the analysis and interpretation of data, and we use AI to summarize papers instead of reading them, and we use it to identify research gaps, and we use AI to review papers for publication or grant applications, then effectively we’re delegating all the thinking to AI platforms.

This hands a terrifying amount of power to AI companies, meaning that Open AI, for example, could easily tweak the algorithm to skew research outputs in any way they want.

And, by the way, many of the AI platforms for academics are just skins built on top of chat GPT… they haven’t actually developed anything new other than the interface, so there’s a lot of power in the hands of very few companies. If this doesn’t worry you, just look at the way Elon Musk took over twitter and imagine the same thing happening with Open AI and the potential knock-on effects on academic publications.

This complete dependence on AI also raises a generation of academics with no meaningful insight or skill other than the ability to engineer AI prompts.

And then there’s the problem of having AI generated papers being assessed by AI. This could easily lead to research being algorithmically optimised to pass AI review and to be cited by other AI-generated papers. This then feeds back into the training data for the large language models, and academia is dead.

The system, as it is, is far from perfect. There are so many problems with the human peer-review system, with predatory journals, with over-worked academics under immense pressure to produce… and while AI might seem to provide a short-term solution, in the long run, I think it makes everything worse.

First, I think we need to be much more skeptical about the promise of AI and the claims made by platforms and those who promote them, especially because many of the people who promote them are being paid to do so and not declaring it in their reviews or recommendations.

Second, we need to do a better job of helping PhD students to develop fundamental skills. A big part of the appeal of AI is that it provides an easy way out when you’re overwhelmed, but if we train students properly in the fundamental skills of research and writing, they’ll be able to use AI to supplement those skills, without being completely dependent on the tech.

I still have faith that even in a time when more and more academics are turning to AI as their first recourse, those with genuine skills and the willingness, with the enthusiasm, to work through difficult problems themselves will be the ones who stand out, because those skills will become rarer and more valuable.

And, third, I think we should maybe start to place greater emphasis on conferences than journal publications.

Conference proceedings have always been perceived as lower value than peer-reviewed journals, but if researchers have to present work to an expert audience and face questions, then they’ll need to know their stuff. It would also make the peer-review process much more open than it currently is.

It would also remove some of the power of publishing companies, who currently charge authors for submission, charge audiences for access, and don’t pay the reviewers they depend upon.

And, perhaps most importantly, it would keep the human element at the heart of academia

PhD: an uncommon guide to research, writing & PhD life is your essential guide to the basic principles every PhD student needs to know.

Applicable to virtually any field of study, it covers everything from finding a research topic, getting to grips with the literature, planning and executing research and coping with the inevitable problems that arise, through to writing, submitting and successfully defending your thesis.

All the text on this site (and every word of every video script) is written by me, personally, because I enjoy writing. I enjoy the challenges of thinking deeply and finding the right words to express my ideas. I do not advocate for the use of AI in academic research and writing, except for very limited use cases.

See also:

Mohammed Hemraj says:

I substantially agree with what has been written. I use AI to review suggestions on what has been written and how I can make an original contribution to the topic, based on my ideas, readings, and gaps I have identified, which I utilise for writing academic books and journal articles.

Helmut Wagabi says:

I would think that we need to concentrate on the ethical use of AI in academia than try to wish it away? Perhaps emphasize verifying whatever sources that AI gives us in a credible library?

James Hayton, PhD says:

Watch the video…